Antonio López de Santa Anna

Antonio López de Santa Anna | |

|---|---|

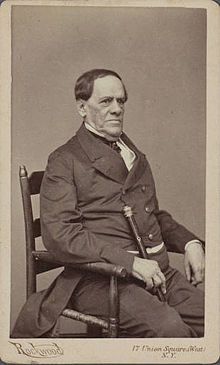

Daguerreotype of Santa Anna, c. 1853 | |

| 8th President of Mexico | |

| In office 20 April 1853 – 5 August 1855 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel María Lombardini |

| Succeeded by | Martín Carrera |

| In office 20 May – 15 September 1847 | |

| Preceded by | Pedro María de Anaya |

| Succeeded by | Manuel de la Peña y Peña |

| In office 21 March – 2 April 1847 | |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Pedro María de Anaya |

| President of the Mexican Republic | |

| In office 4 June – 12 September 1844 | |

| Preceded by | Valentín Canalizo |

| Succeeded by | José Joaquín de Herrera |

| In office 14 May – 6 September 1843 | |

| Preceded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Canalizo |

| In office 10 October 1841 – 26 October 1842 | |

| Preceded by | Francisco Javier Echeverría |

| Succeeded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| In office 20 March – 10 July 1839 | |

| Preceded by | Anastasio Bustamante |

| Succeeded by | Nicolás Bravo |

| President of the United Mexican States | |

| In office 24 April 1834 – 27 January 1835 | |

| Vice President | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Miguel Barragán |

| In office 27 October – 15 December 1833 | |

| Vice President | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| In office 18 June – 5 July 1833 | |

| Vice President | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Preceded by | Valentin Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| In office 17 May – 3 June 1833 | |

| Vice President | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Preceded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Succeeded by | Valentín Gómez Farías |

| Vice President of the Mexican Republic | |

| In office 16 April 1837 – 17 March 1839 | |

| President | Anastasio Bustamante |

| Preceded by | Valentin Gomez Farias |

| Succeeded by | Nicolas Bravo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 21 February 1794 Xalapa, Veracruz, New Spain |

| Died | 21 June 1876 (aged 82) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Resting place | Panteón del Tepeyac, Mexico City |

| Political party | Liberal (until 1833) Conservative (from 1833) |

| Spouses | María Inés de la Paz García

(m. 1825; died 1844)María de los Dolores de Tosta

(m. 1844) |

| Awards | |

| Signature |  |

| Nickname | The Napoleon of the West |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1810–1855 |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | |

Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón, usually known as Antonio López de Santa Anna (Spanish pronunciation: [anˈtonjo ˈlopes ðe sanˈtana]; 21 February 1794 – 21 June 1876),[1] or just Santa Anna,[2] was a Mexican soldier, politician, and caudillo[3] who served as the 8th president of Mexico on multiple occasions between 1833 and 1855. He also served as vice president of Mexico from 1837 to 1839. He was a controversial and pivotal figure in Mexican politics during the 19th century, to the point that he has been called an "uncrowned monarch",[4] and historians often refer to the three decades after Mexican independence as the "Age of Santa Anna".[5]

Santa Anna was in charge of the garrison at Veracruz at the time Mexico won independence in 1821. He would go on to play a notable role in the fall of the First Mexican Empire, the fall of the First Mexican Republic, the promulgation of the Constitution of 1835, the establishment of the Centralist Republic of Mexico, the Texas Revolution, the Pastry War, the promulgation of the Constitution of 1843, and the Mexican–American War. He became well known in the United States due to his role in the Texas Revolution and in the Mexican–American War.

Throughout his political career, Santa Anna was known for switching sides in the recurring conflict between the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party. He managed to play a prominent role in both discarding the liberal Constitution of 1824 in 1835 and in restoring it in 1847. He came to power as a liberal twice in 1832 and in 1847 respectively, both times sharing power with the liberal statesman Valentín Gómez Farías, and both times Santa Anna overthrew Gómez Farías after switching sides to the conservatives. Santa Anna was also known for his ostentatious and dictatorial style of rule, making use of the military to dissolve Congress multiple times and referring to himself by the honorific title of His Most Serene Highness.

His intermittent periods of rule, which lasted from 1832 to 1853, witnessed the loss of Texas, a series of military failures during the Mexican–American War, and the ensuing Mexican Cession. His leadership in the war and his willingness to fight to the bitter end prolonged that conflict: "more than any other single person it was Santa Anna who denied Polk's dream of a short war."[6] Even after the war was over, Santa Anna continued to cede national territory to the Americans through the Gadsden Purchase in 1853.

After he was overthrown and exiled in 1855 through the liberal Plan of Ayutla, Santa Anna began to fade into the background in Mexican politics even as the nation entered the decisive period of the Reform War, the Second French Intervention in Mexico, and the establishment of the Second Mexican Empire. An elderly Santa Anna was allowed to return to the nation by President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada in 1874, and he died in relative obscurity in 1876.

Historians debate the exact number of his presidencies, as he would often share power and make use of puppet rulers; biographer Will Fowler gives the figure of six terms[7] while the Texas State Historical Association claims five.[1] Historian of Latin America, Alexander Dawson counts eleven times that Santa Anna assumed the presidency, often for short periods.[8] The University of Texas Libraries cites the same figure of eleven times, but adds Santa Anna was only president for six years due to short terms.[9]

Santa Anna's legacy has subsequently come to be viewed as profoundly negative, with historians and many Mexicans ranking him as "the principal inhabitant even today of Mexico's black pantheon of those who failed the nation".[10] He is considered one of the most unpopular and controversial Mexican presidents of the 19th century.

Early life

[edit]Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón was born in Xalapa, Veracruz, Nueva España (New Spain), on 21 February 1794 into a respected Spanish family. He was named after his father, licenciado Antonio López de Santa Anna y Pérez (born 1761), a university graduate and a lawyer; his mother was Manuela Pérez de Lebrón y Cortés (died 1814).[11]

Santa Anna's family prospered in Veracruz, where the merchant class dominated politics. His paternal uncle, Ángel López de Santa Anna, was a public clerk (escribano) and became aggrieved when the town council of Veracruz prevented him from moving to Mexico City to advance his career. Since the late 18th-century Bourbon Reforms, the Spanish crown had favored peninsular-born Spaniards over American-born; young Santa Anna's family was affected by the growing disgruntlement of creoles whose upward mobility was thwarted.[12][13]

Santa Anna's mother favored her son's choice of a military career, supporting his desire to join the Spanish Army, rather than be a shopkeeper as his father preferred. His mother's friendly relationship with the intendant (governor) of Veracruz secured Santa Anna's military appointment despite the fact that he was underage. His parents' marriage produced seven children, four sisters and two brothers, and Santa Anna was close to his sister Francisca and brother Manuel, who also joined the army.[14]

Career

[edit]Santa Anna's origins on Mexico's eastern coast had important ramifications for his military career, as he had developed immunity from yellow fever, endemic to the region. The port of Veracruz and environs were known to be unhealthy for those not native to the region,[15][16] so he had a personal strategic advantage against military officers from elsewhere. Being an officer in a time of war was a way that a provincial, middle-class man could vault from obscurity to a position of leadership. Santa Anna distinguished himself in battle, a path that led him to a national political career.[17]

Santa Anna's provincial origins made him uncomfortable in the halls of power in Mexico City, which were dominated by cliques of elite men, and thus he frequently made retreats to his base in Veracruz. He cultivated contact with ordinary Mexican men and pursued entertainments such as cockfighting. Over his career, Santa Anna was a populist caudillo, a strongman wielding both military and political power, similar to others who emerged in the wake of Spanish American wars of independence.[18]

War of Independence, 1810–1821

[edit]Santa Anna's early military career during the Mexican War of Independence, which entailed fighting the insurgency before switching sides against the crown, presaged his many shifts in allegiance during his later political career. In June 1810, the 16-year-old Santa Anna joined the Fijo de Veracruz infantry regiment.[19] In September of that year, secular cleric Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla sparked a spontaneous mass uprising in the Bajío, Mexico's rich agricultural area. Although some creole elites had chafed as their upward mobility had been thwarted by the Bourbon Reforms, the Hidalgo Revolt saw most creoles favoring continued crown rule. In particular, Santa Anna's family "saw themselves as aligned to the peninsular elite, whom they served, and were in turn recognized as belonging".[20]

Initially Santa Anna, like most creole military officers, fought for the crown against the mixed-raced insurgents for independence; his commanding officer was Colonel José Joaquín de Arredondo. In 1811 he was wounded in the left hand by an arrow while fighting in the town of Amoladeras, in the intendancy (administrative district) of San Luis Potosí. In 1813 he served in Texas against the Gutiérrez–Magee Expedition and at the Battle of Medina, in which he was cited for bravery. Santa Anna was promoted quickly; he became a second lieutenant in February 1812 and first lieutenant before the end of that year. During the initial rebellion, the young officer witnessed Arredondo's fierce counterinsurgency policy of mass executions. The early fighting against the rebels gave way to guerrilla warfare and a military stalemate.[21]

When royalist officer Agustín de Iturbide switched sides in 1821 and allied with insurgent Vicente Guerrero, fighting for independence under the Plan of Iguala, Santa Anna also joined the fight for independence. Political developments in Spain, where liberals had ousted King Ferdinand VII and began implementing the Spanish liberal constitution of 1812, made many elites in Mexico reconsider their options.[22]

Rebellion against the Mexican Empire of Iturbide, 1822–1823

[edit]Iturbide, now Emperor Augustin I, rewarded Santa Anna with the command of the vital port of Veracruz, the gateway from the Gulf of Mexico to the rest of the nation and site of a customs house. However, Iturbide subsequently removed Santa Anna from the post, prompting Santa Anna to rise in rebellion in December 1822 against Iturbide. He already had significant power in his home region of Veracruz, and "he was well along the path to becoming the regional caudillo."[23] Santa Anna claimed in his Plan of Veracruz that he rebelled because Iturbide had dissolved the Constituent Congress. He also promised to support free trade with Spain, an important principle for his home region of Veracruz.[24][25]

Although Santa Anna's initial rebellion was important, Iturbide had loyal military men who were able to hold their own against the rebels in Veracruz. However, former insurgent leaders Guerrero and Nicolás Bravo, who had supported Iturbide's Plan de Iguala, returned to their base in southern Mexico and raised a rebellion against Iturbide. The commander of imperial forces in Veracruz, who had fought against the rebels, changed sides and joined the rebels. The new coalition proclaimed the Plan of Casa Mata, which called for the end of the monarchy, restoration of the Constituent Congress, and creation of a republic and a federal system.[26]

No longer the main player in the movement against Iturbide or the creation of new political arrangements, Santa Anna sought to regain his position as a leader and marched forces to Tampico, then to San Luis Potosí, proclaiming his role as the "protector of the federation". Representatives from San Luis Potosí and other north-central regions, such as Michoacán, Querétaro, and Guanajuato, met to decide their own position towards the federation. Santa Anna pledged his military forces to the protection of these key areas. "He attempted, in other words, to co-opt the movement, the first of many examples in his long career where he placed himself as the head of a generalized movement so it would become an instrument of his advancement."[27]

Santa Anna and the early Mexican Republic

[edit]In May 1823, following Iturbide's abdication as emperor in March, Santa Anna was sent to command in Yucatán. At the time, Yucatán's capital of Mérida and the port city of Campeche were in conflict. Yucatán's closest trade partner was Cuba, a Spanish colony. Santa Anna took it upon himself to plan a landing force from Yucatán in Cuba, which he envisioned would result in Cuban colonists welcoming their "liberators", most especially himself. One thousand Mexicans were already on ships to sail to Cuba when word came that the Spanish were reinforcing their colony, so the invasion was called off.[28]

Former insurgent general Guadalupe Victoria, a liberal federalist, became the first president of the Mexican republic in 1824, following the creation of the constitution of 1824. Victoria came to the presidency with little factional conflict, and served out his entire four-year term. However, the election of 1828 was quite different, with considerable political conflict in which Santa Anna became involved.

Even before the election, there was unrest in Mexico, with some conservatives affiliated with the Scottish Rite Freemasons plotting rebellion. The so-called Montaño rebellion in December 1827 called for the prohibition of secret societies, implicitly meaning liberal York Rite Freemasons, and the expulsion of U.S. diplomat Joel Roberts Poinsett, a promoter of federal republicanism. Although Santa Anna was believed to be a supporter of the Scottish Rite conservatives, and Santa Anna was himself a member of the Scottish Rite,[29][30] in the Montaño rebellion he eventually threw his support to the liberals. In his home state of Veracruz, the governor had thrown his support to the rebels, and in the aftermath of the rebellion's failure, Santa Anna as vice-governor stepped into the governorship.[31]

In the 1828 election, Santa Anna supported Guerrero, who was a candidate for the presidency. Another important liberal, Lorenzo de Zavala, also supported Guerrero. However, conservative Manuel Gómez Pedraza won the indirect elections for the presidency, with Guerrero coming in second. Even before all the votes had been counted, Santa Anna raised a rebellion and called for the nullification of the election results, as well for a new law expelling Spanish nationals who he believed to have been in league with the conservatives. The rebellion initially had few supporters, although southern Mexican leader Juan Álvarez soon Santa Anna, while Zavala, under threat of arrest by the conservative Senate, fled to the mountains and organized his own rebellion. Zavala brought the fighting into Mexico City, with his supporters seizing an armory, the Acordada. President-elect Gómez Pedraza resigned and soon after went into exile, clearing the way for Guerrero to assume office. Santa Anna gained prominence for his role in Gómez Pedraza's ouster, and was lauded as a defender of federalism and democracy.[32]

In 1829, Spain made a final attempt to retake Mexico, invading Tampico with a force of 2,600 troops. Santa Anna marched against the Barradas Expedition with a much smaller force and defeated the Spaniards, many of whom were suffering from yellow fever. The defeat of the Spanish Army not only firmly established Santa Anna as a national hero but also consolidated the independence of the new Mexican republic. From this point forward, Santa Anna styled himself the "Victor of Tampico" and the "Savior of the Patria". His main act of self-promotion was to call himself the "Napoleon of the West".

Three months later, in December 1829, Vice-president Anastasio Bustamante, a conservative, mounted a successful coup d'etat against President Guerrero, who left Mexico City to lead a counter-rebellion in the south. Guerrero was captured and executed after a summary trial in 1831, which shocked the nation.[33] In 1832, Santa Anna seized the customs revenues from Veracruz and declared himself in rebellion against Bustamante. The bloody conflict ended with Santa Anna forcing the resignation of Bustamante's cabinet, and an agreement was brokered for new elections in 1833.[34]

"Absentee President", 1833–1835

[edit]

Santa Anna was elected president on 1 April 1833, but while he desired the title, he was not interested in governing. According to Mexican historian Enrique Krauze, "It annoyed him and bored him, and perhaps frightened him."[35] A biographer of Santa Anna describes his role during this period as the "absentee president".[36] Vice-president Valentín Gómez Farías took over the responsibility of governing the nation while Santa Anna retired to Manga de Clavo, his hacienda in Veracruz. Gómez Farías was a moderate, but he had a radical liberal congress with which to contend, perhaps a reason that Santa Anna left executive power to him.[37]

Mexico was faced with an empty treasury and an 11 million peso debt incurred by the Bustamante government. Gómez Farías could not cut back on the bloated expenditures on the army and sought other revenues. Taking a chapter out of the late Bourbon Reforms, he targeted the Roman Catholic Church. Anticlericalism was a tenet of Mexican liberalism, and the church had supported Bustamante's government, so targeting that institution was a logical move. Tithing (a 10% tax on agricultural production) was abolished as a legal obligation, and church property and finances were seized. The church's role in education was reduced and the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico closed. All this caused concern among Mexican conservatives.[38]

Gómez Farías sought to extend these reforms to the frontier province of Alta California, promoting legislation to secularize the Franciscan missions there. In 1833 he organized the Híjar-Padrés colony to bolster non-mission civilian settlement, as well as defend the province against perceived Russian colonial ambitions from the trading post at Fort Ross.[39] However, for liberal intellectual and Catholic priest José María Luis Mora, selling church property was the key to "transforming Mexico into a liberal, progressive nation of small landowners." Sale of nonessential church property would bring in much-needed revenue to the treasury. The army was also targeted for reform, since it was the largest single expenditure in the national budget. On Santa Anna's suggestion, the number of battalions was to be reduced as well as the number of generals and brigadiers.[40]

The government soon issued a law, the Ley del Caso, which called for the arrest of 51 politicians, including Bustamante, for holding "unpatriotic" beliefs and their expulsion from the country. Gómez Farías claimed that Santa Anna was the driving force for the law, which evidence seems to support.[41] With increasing resistance from the church as well as the army, the Plan of Cuernavaca was issued, likely orchestrated by former general and governor of the Federal District, José María Tornel. The plan called for repeal of the Ley del Caso; discouraged tolerance of the influence of Masonic lodges, where politics was pursued in secrecy; declared void the laws passed by Congress and the local legislatures in favor of the reforms; requested the protection of Santa Anna to fulfill the plan and recognize him as the only authority; removed from office deputies and officials who carried out enforcement of the reform laws and decrees; and provided military force to support Gómez Farías in implementing the plan.[42]

As opinion turned against the reforms, Santa Anna was persuaded to return to the presidency and Gómez Farías resigned. This set the stage for conservatives to reshape Mexico's government from a federalist republic to a unitary central republic.[43]

Central Republic, 1835

[edit]

For conservatives, the liberal reform of Gómez Farías was radical and threatened the power of the elites. Santa Anna's actions in allowing this first reform (followed by a more sweeping one in 1855) might have been a test case for liberalism. At this point, Santa Anna was a liberal; by giving the moderate Gómez Farías responsibility for the reforms, he could have plausible deniability and closely monitor the reaction to a comprehensive attack on the special privileges of the army and the church, as well as confiscation of church wealth, enacted by Congress.

In May 1834, Santa Anna ordered the disarmament of the civic militia and urged Congress to abolish the controversial Ley del Caso.[44] On 12 June he dissolved Congress and announced his decision to adopt the Plan of Cuernavaca, forming a new Catholic, centralist and conservative government.[45] Santa Anna brokered a deal where, in exchange for preserving the privileges of the church and the army, the church promised a monthly donation to the government of 30,000–40,000 pesos.[46] "The santanistas [supporters of Santa Anna] succeeded in achieving what the radicals had failed to do: forcing the Church to assist the republic's daily fiscal needs with its funds and properties."[47]

On 4 January 1835, Santa Anna returned to his hacienda, placing Miguel Barragán as acting president. He soon replaced the 1824 constitution with the new document known as the "Siete Leyes" ("The Seven Laws"). Santa Anna did not involve himself with the conservative effort to replace the federalist constitution with a unitary central government, seemingly uneasy with their political path. "Although he has been blamed for the change to centralism, he was not actually present during any of the deliberations that led to the abolition of the federalist charter or the elaboration of the 1836 Constitution."[48][49]

Several states openly rebelled against the changes, including Alta California, Nuevo México, Tabasco, Sonora, Coahuila y Tejas, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, Durango, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Yucatán, Jalisco, Nuevo León, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas. Several of these states formed their own governments: the Republic of the Rio Grande, the Republic of Yucatán, and the Republic of Texas. Their fierce resistance was possibly fueled by Santa Anna's reprisals committed against his defeated enemies.[50] The New York Post editorialized that "had Santa Anna treated the vanquished with moderation and generosity, it would have been difficult if not impossible to awaken that general sympathy for the people of Texas which now impels so many adventurous and ardent spirits to throng to the aid of their brethren."[51]

The Zacatecas militia, the largest and best supplied of the Mexican states, led by Francisco García Salinas, was well armed with .753 caliber British 'Brown Bess' muskets and Baker .61 rifles. But, after two hours of combat on 12 May 1835, Santa Anna's "Army of Operations" defeated the Zacatecan militia and took almost 3,000 prisoners. He allowed his army to loot Zacatecas City for forty-eight hours. After conquering Zacatecas, he planned to move on to Coahuila y Tejas to quell the rebellion there, which was being supported by settlers from the United States.[citation needed]

Texas Revolution 1835–1836

[edit]

In 1835, Santa Anna repealed the Mexican constitution, which ultimately led to the beginning of the Texas Revolution. His reasoning for the repeal was that American settlers in Texas were not paying taxes or tariffs, claiming they were not recipients of any services provided by the Mexican government; as a result, new settlers were not allowed there. The new policy was a response to the U.S. attempts to purchase Texas from Mexico.[52] Like other states discontented with the central government, the Texas Department of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas rebelled in late 1835 and declared itself independent on 2 March 1836. The northeastern part of the state had been settled by numerous American immigrants. Moses Austin, the father of Stephen F. Austin, had his party accepted by Spanish authorities in exchange for defense against foreign threats. However, Mexico had declared independence from Spain before the elder Austin died.[citation needed]

Santa Anna marched north to bring Texas back under Mexican control by a brutal show of force. His expedition posed challenges of manpower, logistics, supply and strategy far beyond what he was prepared for, and it ended in disaster. To fund, organize and equip his army, Santa Anna relied, as he often did, on forcing wealthy men to "loan" him funds. He recruited hastily, sweeping up many derelicts and ex-convicts, as well as Indians who could not understand Spanish commands.[citation needed]

Having expected tropical weather, Santa Anna's army suffered from cold, a lack of proper clothing and food shortages. Stretching a supply line far longer than ever before, there were not enough horses, mules, cattle and wagons available, resulting in units never having enough food, fuel, or feed. The medical facilities were minimal and poorly supplied. Morale sank as soldiers realized there were not enough chaplains to properly bury their bodies. Hostile Indians picked off stragglers and foragers. Waterborne sicknesses spread quickly when the men were forced to drink any water they could find on the trail. The officers proved to be mostly incompetent, yet the highly insulated and rigid hierarchy of the army meant that Santa Anna was kept ignorant of these problems.[53]

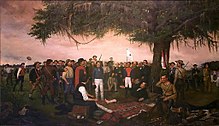

Santa Anna's forces killed 189 Texan defenders at the Battle of the Alamo on 6 March 1836, and executed more than 342 Texan prisoners at the Goliad Massacre on 27 March 1836. However, his forces suffered unexpectedly heavy casualties. In an 1874 letter, Santa Anna asserted that killing the defenders of Alamo was his only option, stressing that Texan commander William B. Travis was to blame for the degree of violence during the battle. Santa Anna believed that Travis was disrespectful towards him, and that if he had spared the Texans, it would have allowed Sam Houston to establish a dominant position that could threaten him later.[54]

The Mexican victory at the Alamo bought time for Houston and his Texas forces. During the siege, the Texian Navy had more time to plunder ports along the Gulf of Mexico, and the Texian Army gained more experience and weaponry. Despite Houston's lack of ability to maintain strict control of the Army, they completely routed Santa Anna's much larger army at the Battle of San Jacinto on 21 April 1836. The day after the battle, a small Texan force led by James Austin Sylvester captured Santa Anna near a marsh; the general had hastily dressed himself in a dead Mexican dragoon's uniform but was quickly recognized.[citation needed]

After three weeks in captivity,[55] Texas President David G. Burnet and Santa Anna signed the Treaties of Velasco stating that "in his official character as chief of the Mexican nation, he acknowledged the full, entire, and perfect Independence of the Republic of Texas." In exchange, Burnet and the Texas government guaranteed Santa Anna's safety and transport to Veracruz. Meanwhile, in Mexico City, a new government declared that Santa Anna was no longer president and that the Treaties were null and void. While Santa Anna was held captive in Texas, Poinsett offered a harsh assessment of his situation: "Say to General Santa Anna that when I remember how ardent an advocate he was of liberty ten years ago, I have no sympathy for him now, that he has gotten what he deserves." Santa Anna replied: "Say to Mr. Poinsett that it is very true that I threw up my cap for liberty with great ardor, and perfect sincerity, but very soon found the folly of it. A hundred years to come my people will not be fit for liberty. They do not know what it is, unenlightened as they are, and under the influence of Catholic clergy, a despotism is a proper government for them, but there is no reason why it should not be a wise and virtuous one."[56]

Redemption, dictatorship, and exile

[edit]

After some time in exile, and after meeting U.S. President Andrew Jackson in 1837, Santa Anna was allowed to return to Mexico. He was transported aboard the USS Pioneer to retire to his hacienda in Veracruz. There he wrote a manifesto in which he reflected on his experiences and decision-making in Texas.[57][58]

In 1838, Santa Anna found a chance for redemption from the loss of Texas. After Mexico rejected demands for financial compensation for losses suffered by its citizens, France sent forces that landed in Veracruz in the Pastry War. The Mexican government gave Santa Anna control of the army and ordered him to defend the nation by any means necessary. Santa Anna engaged the French at Veracruz but was forced to retreat after a failed assault, sustaining injuries in his left leg and hand by cannon fire. His shattered ankle required amputation of much of his leg, which he ordered buried with full military honors.[59] Despite Mexico's final capitulation to French demands, Santa Anna used his war service and visible sacrifice to the nation to re-enter Mexican politics.[citation needed]

Soon after, with Bustamante's presidency descending into chaos, supporters asked Santa Anna to take control of the provisional government. Santa Anna was made president for the fifth time, taking over a nation with an empty treasury. The war with France had weakened the country, and the people were discontented. Also, a rebel army led by Generals José de Urrea and José Antonio Mexía, was marching towards Mexico City in opposition to Santa Anna. Commanding the army, Santa Anna crushed the rebellion in Puebla.[citation needed]

Santa Anna ruled in a more dictatorial fashion than during his first administration. His government banned anti-Santanista newspapers and jailed dissidents to suppress opposition. In 1842, he directed a military expedition into Texas. The action inflicted numerous casualties with no political gain, but Texans began to be persuaded of the potential benefits of annexation by the more powerful U.S.[citation needed]

Following the 1842 elections, at which a new Congress was elected which opposed his rule,[60] Santa Anna attempted to restore the treasury by raising taxes. Several Mexican states stopped dealing with the central government in response, and Yucatán and Laredo declared themselves independent republics. With resentment growing, Santa Anna stepped down and fled Mexico City in December 1844. The buried leg he left behind in the capital was dug up by a mob and dragged through the streets until nothing was left of it.[61][62] Fearing for his life, Santa Anna tried to elude capture, but in January 1845 he was apprehended by a group of Native Americans near Xico. They turned him over to authorities, and he was imprisoned. Santa Anna's life was ultimately spared, but he was exiled to Cuba.[citation needed]

Mexican–American War, 1846–1848

[edit]

In 1846, following American victories at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma in the Mexican-American War, President Mariano Paredes was removed from office, with the new government seeking to reinstate the constitution of 1824, with Santa Anna again assuming the presidency. Santa Anna, who had been in exile for only a year, returned to Mexico on 6 August 1846, two days after Paredes' ouster. He wrote to the new government stating he had no aspirations to the presidency but would eagerly use his military experience in the new conflict with the U.S.

U.S. President James K. Polk had hoped to acquire territory in the north by purchase or force, but the Mexican government was not willing to yield. In a gambit to change the dynamic, Polk sent agents to secretly meet with the exiled Santa Anna. They thought they had extracted a promise from him that they would lift a blockade of the Mexican coast to allow him to return and that he would broker a deal. Once back in Mexico at the head of an army, however, Santa Anna reneged on the deal and took up arms against the U.S. invasion.[63]

With no path now for a quick resolution to the conflict in the north, Polk authorized an invasion to take Mexico City, redirecting the bulk of General Zachary Taylor's troops to General Winfield Scott's army. Santa Anna mobilized troops and artillery and rapidly marched north. His forces outnumbered Taylor's, but his troops were exhausted, ill-clothed, hungry and equipped with inferior weapons when the two armies clashed at the Battle of Buena Vista on 22–23 February 1847. Hard fighting over two days brought an inconclusive result, with Santa Anna withdrawing from the field of battle overnight just as complete victory was at hand, taking war trophies such as cannons and battle flags as evidence of his victory. With Scott's army landing at Veracruz, Santa Anna's home ground, he rapidly moved southward to engage with the invaders and protect the capital. For the Mexicans it would have been better if Scott could have been prevented from leaving the Gulf Coast, but they could not prevent Scott's march on Xalapa. Santa Anna set defenses at Cerro Gordo. U.S. forces outflanked him and against strong odds defeated his army.

With that battle, the way was clear for Scott's forces to advance further onto Mexico City. Santa Anna's aim was to protect the capital at all costs and waged defensive warfare, placing strong defenses on the most direct road into the city at El Peñon, which Scott then avoided. Battles at Contreras, Churubusco, and Molino del Rey were lost. At Contreras, Mexican General Gabriel Valencia, an old political and military rival of Santa Anna's, did not recognize his authority as supreme commander and disobeyed his orders as to where his troops should be placed. Valencia's Army of the North was routed. The Battle for Mexico City and the Battle of Chapultepec, like the others, were hard fought losses, and American forces took the capital. "Despite his many faults as a tactician and his overbearing political ambition, Santa Anna was committed to fighting to the bitter end. His actions would prolong the war for at least a year, and more than any other single person it was Santa Anna who denied Polk's dream of a short war."[64]

Perhaps Santa Anna's most personal and ignominious incident in the war was the capture during the Battle of Cerro Gordo of his prosthetic cork leg,[65] which remains as a war trophy in the U.S. held by the Illinois State Military Museum but no longer on display.[66] A second leg, a peg, was also captured by the 4th Illinois and was reportedly used by the soldiers as a baseball bat; it is displayed at the home of Illinois Governor Richard J. Oglesby (who served in the regiment) in Decatur.[67] Santa Anna had a replacement leg made which is displayed at the Museo Nacional de Historia in Mexico City.[68]

The prosthetic leg later played a role in international politics. As relations between the U.S. and Mexico warmed during the run-up to World War II, Illinois was rumored to be ready to return the prosthetic to Mexico and, in 1942, a bill was introduced in the state legislature. The Association of Limb Manufacturers wanted to be part of the repatriation ceremonies. The state passed a non-binding resolution to return the prosthetic, but the National Guard denied the transfer.[69] As of 2016 the leg still resided in the Illinois State Military Museum in Springfield.[70]

President for the last time, 1853–1855

[edit]

Following Mexico's defeat in 1848, Santa Anna went into exile in Kingston, Jamaica. Two years later, he moved to Turbaco in New Granada (now Colombia). In April 1853, he was invited to return to Mexico by conservatives who had overthrown a weak liberal government, initiated under the Plan de Hospicio, drawn up by the clerics in the cathedral chapter of Guadalajara. Usually, revolts were fomented by military officers; this one was fomented by churchmen.[71] Santa Anna was elected president on 17 March 1853. He honored his promises to the church, revoking a decree denying protection for the fulfillment of monastic vows, a reform promulgated twenty years earlier by Gómez Farías.[72] The Jesuits, who had been expelled from Spanish realms by the crown in 1767, were allowed to return to Mexico ostensibly to educate poorer classes, and much of their property, which the crown had confiscated and sold, was restored to them.[72]

Although he gave himself exalted titles, Santa Anna's situation was quite vulnerable. He declared himself dictator-for-life with the title "Most Serene Highness". His full title in this final period of power was "Hero [benemérito] of the nation, General of Division, Grand Master of the National and Distinguished Order of Guadalupe, Grand Cross of the Royal and Distinguished Spanish Order of Carlos III, and President of the Mexican Republic."[73] The reality was that this administration was no more successful than his earlier ones, dependent on loans from moneylenders and support from conservative elites, the church, and the army.

A major miscalculation was Santa Anna's sale of territory to the U.S. in what became known as the Gadsden Purchase. La Mesilla, the land in northwest Mexico that the U.S. wanted, was much easier terrain for the building of a transcontinental railway in the U.S. The purchase money for the land was supposedly to go to Mexico's empty treasury. Santa Anna was unwilling to wait until the final transaction went through and the boundary line established, wanting access to the money immediately. He bargained with American bankers to get immediate cash, while they gained the right to the revenue when the sale closed. Santa Anna's short-sighted deal netted the Mexican government only $250,000 against credit of $650,000 going to the bankers. James Gadsden thought the amount was likely much higher.[74] A group of liberals including Alvarez, Benito Juárez, and Ignacio Comonfort overthrew Santa Anna under the Plan of Ayutla, which called for his removal from office. He went into exile yet again in 1855.

By the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the United States paid Mexico only $15 million for the stolen land, in which became known as the Mexican Cession.

Personal life

[edit]

Santa Anna married twice, both times to wealthy young women. At neither wedding ceremony did he appear, legally empowering his future father-in-law to serve as a proxy at his first wedding and a friend at his second.[75] One assessment of the two marriages is that they were arranged marriages of convenience, bringing considerable wealth to Santa Anna and that his lack of attendance at the ceremonies "appears to confirm that he was purely interested in the financial aspect o[f] the alliance."[76]

In 1825, Santa Anna married Inés García, the daughter of wealthy Spanish parents in Veracruz, and the couple had four children: María de Guadalupe, María del Carmen, Manuel, and Antonio López de Santa Anna y García.[77] By 1825, Santa Anna had distinguished himself as a military man, joining the movement for independence. When Iturbide lost support, Santa Anna had been in the forefront of leaders seeking to oust him. Although his family was of modest means, Santa Anna was of good creole lineage; the García family may well have seen a match between their young daughter and the up-and-coming Santa Anna as advantageous. Inés' dowry allowed Santa Anna to purchase the first of his haciendas, Manga de Clavo, in Veracruz.[76][78]

The first Spanish ambassador to Mexico and his wife, Fanny Calderón de la Barca, visited with Inés at Manga de Clavo, where they were well-received with a breakfast banquet. Calderón de la Barca observed that "After breakfast, the Señora having dispatched an officer for her cigar-case, which was gold with a diamond latch, offered me a cigar, which I having declined, she lighted her own, a little paper 'cigarette', and the gentlemen followed her good example."[79]

Two months after the death of his wife Inés in 1844, the 50-year-old Santa Anna married 16-year-old María de Los Dolores de Tosta. The couple rarely lived together; de Tosta resided primarily in Mexico City, and Santa Anna's political and military activities took him around the country.[80] They had no children, leading biographer Will Fowler to speculate that either the marriage was primarily platonic or de Tosta was infertile.[80]

Several women claimed to have borne Santa Anna natural children. In his will, he acknowledged and made provisions for four: Paula, María de la Merced, Petra, and José López de Santa Anna. Biographers have identified three more: Pedro López de Santa Anna, and Ángel and Augustina Rosa López de Santa Anna.[77]

Later years and death

[edit]

From 1855 to 1874, Santa Anna lived in exile in Cuba, the United States, Colombia, and Saint Thomas. He had left Mexico because of his unpopularity with the Mexican people after his defeat in 1848. Santa Anna participated in gambling and businesses with the hopes that he would become rich. During his many years in exile, he was a passionate fan of the sport of cockfighting; he had many roosters that he entered into competitions and would have his roosters compete with cocks from all over the world.[81]

In the 1850s, Santa Anna traveled to New York City with a shipment of chicle, which he intended to sell for use in making carriage wheels. He attempted but was unsuccessful in convincing U.S. wheel manufacturers that this substance could be more useful in tires than the materials they were originally using. Although he introduced chewing gum to the U.S., Santa Anna did not make any money from the product.[81] Thomas Adams, the American assigned to aid Santa Anna while he was in the U.S., experimented with chicle in an attempt to use it as a substitute for rubber. He bought one ton of the substance from Santa Anna, but his experiments proved unsuccessful. Instead, Adams helped to found the chewing gum industry with a product that he called "chiclets".[82]

In 1865, Santa Anna attempted to return to Mexico and offer his services during the French invasion, seeking once again to play the role as the country's defender and savior, only to be refused by Juárez. Later that year a schooner owned by Gilbert Thompson, son-in-law of Daniel Tompkins, brought Santa Anna to his home in Staten Island,[83] where he tried to raise money for an army to return and take over Mexico City.

In 1874, Santa Anna took advantage of a general amnesty issued by President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada and returned to Mexico, by then crippled and almost blind from cataracts. He died at his home in Mexico City on 21 June 1876 at age 82. Santa Anna was buried with full military honors in a glass coffin in Panteón del Tepeyac Cemetery.[citation needed]

Legacy

[edit]

Santa Anna was highly controversial at the time and ever since. In the 2007 biography by Will Fowler, he was depicted as, "a liberal, a Republican, an army man, a hero, a revolutionary, a regional strongman, but never a politician. He presented himself as a mediator who was both anti-party and anti-politics in the decades when the new country of Mexico was wracked by factional infighting. He was always more willing to lead an army than to lead his country".[84]

In popular culture

[edit]- He features in several 19th century British sea shanties, frequently as "santianna", "Santy Anno" or other variations, which have been recorded many times by 20th century folk musicians.

- He is played by Rubén Padilla (Mexican actor, not to be confused with the homonymous American athlete) in the John Wayne film The Alamo.

- Fox animated series King of the Hill season 2 episode 18 "The Final Shinsult" largely revolves around Santa Anna's prosthetic leg.

- In the 1998 film The Mask of Zorro, Santa Anna is mentioned and is portrayed by Joaquim de Almeida in an alternate ending.

- He is played by Emilio Echevarría in the 2004 film The Alamo.

- He is played by J. Carrol Naish in the 1955 film The Last Command.

- He is played by Olivier Martinez in the History Channel's miniseries Texas Rising (2015)

- He is played by Raul Julia in a cast of TV and future stars such as Alec Baldwin in the movie The Alamo: 13 days to glory (1987)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Callcott, Wilfred H., "Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez De," Handbook of Texas Online, Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Howe, Daniel Walker (2007), What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848, Oxford Univ. Press, p. 660

- ^ Warren, Richard. "Antonio López de Santa Anna". Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, v. 5, 48.

- ^ quoted in Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 88.

- ^ Costeloe, Michael P. The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835–1846: Hombres de Bien in the Age of Santa Anna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1993.

- ^ Guardino, Peter. The Dead March: A History of the Mexican-American War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 2017, 88.

- ^ Fowler 2009, p. xxi.

- ^ Dawson, Alexander (2010). Latin America since Independence A History with Primary Sources. Routledge. p. 36. ISBN 9780415991964.

- ^ "Santa Anna in Life and Legend – His Serene Highness and the Absentee President". University of Texas At Austin – University of Texas Libraries. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ^ Archer, Christon I. "Fashioning a New Nation" in Michael C. Meyer and William H. Beezley, eds. The Oxford History of Mexico (2000) p. 322

- ^ "TSHA | Santa Anna, Antonio Lopez de". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ Lockhart, James; Brading, D. A. (May 1992). "The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 72 (2): 277. doi:10.2307/2515558. JSTOR 2515558.

- ^ Lockhart, James (1992). "Reviewed work: The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867., D. A. Brading". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 72 (2): 277–279. doi:10.2307/2515558. JSTOR 2515558.

- ^ Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico. Lincoln: University of Nebraska 2007, pp. 13–17.

- ^ Archer, Christon. The Army in Bourbon Mexico, 1760–1810. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1977, pp. 38–72

- ^ Earle, Rebecca. "A Grave for Europeans? Disease, Death, and the Spanish-American Revolutions," War in History 3 (1996), pp. 371–383

- ^ Fowler, (2007)

- ^ Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 18.

- ^ Pani, Erika. "Antonio López de Santa Anna" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 1334.

- ^ quoted in Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 17.

- ^ Fowler 2009, p. 27.

- ^ Pani, "Antonio López de Santa Anna", p. 1334.

- ^ Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821–1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998, p. 103.

- ^ Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 104.

- ^ Benson, Nettie Lee. "The Plan of Casa Mata", Hispanic American Historical Review 25, no. 1, (February 1945): pp. 45–56.

- ^ Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 107.

- ^ Anna, Forging Mexico, p. 133.

- ^ Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade 1823–1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press (1987), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Walter, Catherine M. (18 January 2017). "Santa Anna's 1825 Scottish Rite Certificate". Grand Lodge of Free & Accepted Masons of the State of New York. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ "Santa Anna's Masonry Confirmed". pubs.royle.com. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- ^ Anna, Forging Mexico, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Anna, Forging Mexico, pp. 218–219, 224.

- ^ Fowler (2007)

- ^ Tenenbaum, The Politics of Penury, p. 37

- ^ Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 137.

- ^ Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico, chapter 7, "The Absentee President, 1832–1835", pp. 133–157

- ^ Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 143.

- ^ Costeloe, Michael P. (1974). "Santa Anna and the Gómez Farías Administration in Mexico, 1833–1834". The Americas. 31 (1): 18–50. doi:10.2307/980380. JSTOR 980380.

- ^ Hutchinson, C. Alan (1969). Frontier Settlement in Mexican California; The Híjar-Padrés Colony and Its Origins, 1769–1835. New Haven: Yale University Press. OCLC 23067.

- ^ Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 145.

- ^ Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 420

- ^ González Pedrero, Enrique (2004). País de un solo hombre: el México de Santa Anna. Volumen II. La sociedad de fuego cruzado 1829–1836 (in Spanish). México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. ISBN 968-16-6377-2.

- ^ Tenenbaum, The Politics of Penury, pp. 38–40.

- ^ González Pedrero 2004, p. 468.

- ^ Olavarría y Ferrari 1880, p. 344.

- ^ Tenenbaum, Barbara. México en la época de los agiotistas, 1821–1857. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1985, p. 64.

- ^ Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 157.

- ^ Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, p. 158

- ^ Costeloe, The Central Republic, 1835–1846, pp. 46–65.

- ^ Edmondson, J.R. The Alamo Story: From Early History to Current Conflicts (2000) p. 378.

- ^ Lord (1961), p. 169.

- ^ Wright, R. "Santa Anna and the Texas Revolution". Andrews University. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- ^ Presley, James. "Santa Anna's Invasion of Texas: A Lesson in Command", Arizona & the West, (1968) 10#3 pp. 241–252

- ^ "Santa Anna to McArdle, March 16, 1874: Letter Explaining Why the Alamo Defenders Had to Be Killed". Texas State Library and Archives Commission. the State of Texas.

- ^ Sproat, Leslie. "Capture site of Santa Anna". East Texas History. Leslie Sproat. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ "Captivity of Antonio Santa Anna". Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2006.

- ^ tamu.edu, "Manifesto which General Antonio Lopez De Santa Anna Addresses to His Fellow Citizens",

- ^ "Manifesto". sonsofdewittcolony.org. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Shoup, Kate (2015). Texas and the Mexican War. Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 9781502609649. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Costeloe, Michael P. (1989). "Generals versus Politicians: Santa Anna and the 1842 Congressional Elections in Mexico". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 8 (2): 257–274. doi:10.2307/3338755. JSTOR 3338755.

- ^ Camnitzer 2009.

- ^ Fowler 2009, p. 239.

- ^ Fowler, Santa Anna of Mexico, pp. 256–257

- ^ Guardino The Dead March, p. 88.

- ^ Flight of Santa Anna showing him without his prosthetic leg accessed 28 May 2020

- ^ Wagenen, Michael Scott. Remembering the Forgotten War: The Enduring Legacies of the U.S.-Mexican War. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press 2012, pp. 26, 157–158, 232–233

- ^ "Captured Leg of Santa Anna", Roadside America

- ^ "Santa Anna's Leg Took a Long Walk", Latin American Studies

- ^ Wagenen, Michael Scott. Remembering the Forgotten War: The Enduring Legacies of the U.S.-Mexican War. Amherst, University of Massachusetts Press 2012, pp. 157–158

- ^ "Santa Anna's leg? Come and take it". Chicago Tribune. 11 November 2016.

- ^ Lloyd (1966). Church and State in Latin America, revised edition. Chapel Hill: the University of North Carolina Press. p. 358.

- ^ a b Mecham, Church and State, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Mecham, Church and State, p. 359.

- ^ Tenenbaum, The Politics of Penury, p. 138

- ^ Fowler, Will. "All the President's Women: The Wives of General Antonio Santa Anna in 19th century Mexico", Feminist Review, No. 79, Latin America: History, war, and independence (2005), pp. 57–58.

- ^ a b Fowler, "All the President's Women", p. 58.

- ^ a b Fowler 2009, p. 92.

- ^ Potash, Robert. "Testaments de Santa Anna." Historia Mexicana, Vol. 13, No. 3, 430–440.

- ^ Calderón de la Barca, F. Life in Mexico. London: Century, pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b Fowler 2009, p. 229.

- ^ a b Mead, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America. UK: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-1405120517.

- ^ "The New York Public Library". The New York Public Library. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011.

- ^ Mex general's Staten ex-isle Retrieved 22 November 2018

- ^ Review by Patricia L. P. Thompson, The Historian, (2010) 72#1, p. 198

Sources

[edit]- Camnitzer, Luis (2009). Weiss, Rachel (ed.). On Art, Artists, Latin America, and Other Utopias. University of Texas Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780292783492.

- Fowler, Will (2000). Tornel and Santa Anna: the writer and the caudillo, Mexico, 1795–1853. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-313-30914-4.[permanent dead link]

- Fowler, Will (2009). Santa Anna of Mexico. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2638-8.

- Olavarría y Ferrari, Enrique de (1880). Vicente Riva Palacio (ed.). México a través de los siglos (in Spanish). México: Ballescá y Cía. pp. 210–226.

- Mead, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America (2 ed.). UK: John Wiley & Sons Inc. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-1405120517.

Further reading

[edit]- Alemán, Jesse. "The Ethnic in the Canon; or, on Finding Santa Anna's" Wooden Leg"." MELUS 29.3/4 (2004): 165–182.

- Anna, Timothy E. Forging Mexico, 1821–1835. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1998

- Calcott, Wilfred H. Santa Anna: The Story of the Enigma Who Once Was Mexico. Hamden CT: Anchon, 1964.

- Camnitzer, L. "The two versions of Santa Anna's leg and the ethics of public art." On art, artists, Latin America and other utopias (1995): 199–207. ISBN 9780292783492

- Chartrand, Rene, and Younghusband, Bill. Santa Anna's Mexican Army 1821–48 (2004) excerpt and text search

- Cole, David A. "The Early Career of Antonio López de Santa Anna," PhD dissertation. Christ Church, University of Oxford 1977.

- Costeloe, Michael P. The Central Republic in Mexico, 1835–1846: Hombres de Bien in the Age of Santa Anna. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1993.

- Crawford, Ann F.; The Eagle: The Autobiography of Santa Anna; State House Press;

- Díaz Díaz, Fernando. Caudillos y caciques: Antonio López de Santa Anna y Juan Álvarez. Mexico City: El Colegio de México 1972.

- Flores Mena, Carmen. El general don Antonio López de Santa Anna (1810–1833). Mexico City: UNAM 1950.

- Fowler, Will (2007), Santa Anna of Mexico, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; a favorable scholarly biography

- Fowler, Will. Mexico in the Age of Proposals, 1821–1853 (1998)

- Fowler, Will. Tornel and Santa Anna: The Writer and the Caudillo, Mexico, 1795–1853 (2000) excerpt and text search

- Fowler, Will. "All the President's Women: The Wives of General Antonio López de Santa Anna in 19th century Mexico", Feminist Review, No. 79, Latin America: History, war, and independence (2005),

- Fuentes Mares, José. Santa Anna: Aurora y ocaso de un comediante. Mexico City: Jus 1956.

- González Pedrero, Enrique. País de un solo hombre: el México de Santa Anna. Volumen II. La sociedad de fuego cruzado 1829–1836. Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City 2004. ISBN 968-16-6377-2

- Green, Stanley C. The Mexican Republic: The First Decade 1823–1832. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 1987

- Hardin, Stephen L., and McBride, Angus. The Alamo 1836: Santa Anna's Texas Campaign (2001) excerpt and text search

- Jackson, Jack. "Santa Anna's 1836 Campaign: Was It Directed Toward Ethnic Cleansing?" Journal of South Texas (March 2002) 15#1 pp. 10–37; argues that it was

- Jackson, Jack, and Wheat, John. Almonte's Texas, Texas State Historical Assoc.

- Jones, Oakah L., Jr. Santa Anna. New York: Twayne Publishers 1968.

- Knight, Alan. "The Several Legs of Santa Anna: A Saga of Secular Relics." Past & Present, Volume 206, Issue suppl_5, 2010, pp. 227–255, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtq019

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997. ISBN 0-06-016325-9

- Lord, Walter (1961), A Time to Stand, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-7902-7, popular history

- Mabry, Donald J., "Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna", 2 November 2008; essay by scholar

- Muñoz, Rafael F. Santa Anna: El dictador resplandeciente. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica 1983.

- Paquel, Leonardo. Antonio López de Santa Anna. Mexico City: Instituto de Mexicología 1990.

- Roberts, Randy & Olson, James S., A Line in the Sand: The Alamo in Blood and Memory (2002)

- Santoni, Pedro; Mexicans at Arms-Puro Federalist and the Politics of War TCU Press; [ISBN missing]

- Scheina, Robert L. Santa Anna: A Curse Upon Mexico Washington, D.C.: Brassey's 2003. excerpt and text search

- Trueba, Alfonso. Santa Anna. Mexico City: Jus 1958.

- Valadés, José C. México, Santa Anna, y la guerra de Texas. Mexico City: Editorial Diana 1979.

- Vázquez, Josefina Zoraida. Don Antonio López de Santa Anna: Mito y enigma. Mexico City: Condumex 1987.

- Yañez, Agustín. Santa Anna: Espectro de una sociedad. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica 1993.

External links

[edit]- Santa Anna Letters on the Portal to Texas History

- Antonio López de Santa Anna in A Continent Divided: The U.S. – Mexico War, Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna

- Benson Latin American Collection – Antonio López de Santa Anna Collection

- Sketch of Santa Anna from A pictorial history of Texas, from the earliest visits of European adventurers to A.D. 1879, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Archontology.org, Home » Nations » Mexico » Heads of State » LÓPEZ de SANTA ANNA, Antonio

- Texas Prisoners in Mexico 3 August 1843 From Texas Tides

- Presidents of Mexico

- Vice presidents of Mexico

- Leaders who took power by coup

- People from New Spain

- Mexican generals

- Mexican military personnel of the Mexican–American War

- Conservatism in Mexico

- 1794 births

- 1876 deaths

- 19th-century presidents of Mexico

- Mexican amputees

- Mexican independence activists

- Generalissimos

- Governors of Veracruz

- Governors of Yucatán (state)

- Exiled Mexican politicians

- Candidates in the 1833 Mexican presidential election

- Recipients of Mexican presidential pardons

- Politicians from Xalapa

- Mexican Republic combatants of the Texas Revolution

- People of the Second French intervention in Mexico

- Mexican Freemasons