Little Russia

| Little Russia Малая Русь | |

|---|---|

| Region of the Russian Empire | |

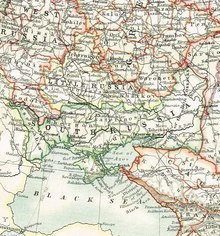

A fragment of the “new and accurate map of Europe collected from the best authorities...” by Emanuel Bowen published in 1747 in his A complete system of geography. The territory around Voronezh and Tambov is shown as “Little Russia”. White Russia is located north-east of Smolensk, and the legend “Ukrain” straddles the Dnieper river near Poltava. | |

| Today part of | Belarus Russia Ukraine Moldova |

Little Russia,[a] also known as Lesser Russia, Malorussia, or Little Rus',[b] is a geographical and historical term used to describe Ukraine.[2]

At the beginning of the 14th century, the patriarch of Constantinople accepted the distinction between what it called the eparchies of Megalē Rosiia (lit. 'Great Rus, Great Russia') and Mikrà Rosiia (lit. 'Little Rus, Little Russia').[1][3][4] The jurisdiction of the latter became the metropolis of Halych in 1303.[1] The specific meaning of the adjectives "Great" and "Little" in this context is unclear. It is possible that terms such as "Little" and "Lesser" at the time simply meant geographically smaller and/or less populous,[5] or having fewer eparchies.[3] Another possibility is that it denoted a relationship similar to that between a homeland and a colony (just as "Magna Graecia" denoted a Greek colony).[3]

The name went out of use in the 15th century as distinguishing the "Great" and "Little" was no longer necessary since the Russian Orthodox Church based in Moscow was no longer tied to Kiev. However, with the rise of the Catholic Ruthenian Uniate Church in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Orthodox prelates attempting to seek support from Moscow revived the name using the Greek-influenced spelling: Malaia Rossiia ("Little Russia").[3] Then, "Little Russia" developed into a political and geographical concept in Russia, referring to most of the territory of modern-day Ukraine, especially the territory of the Cossack Hetmanate. Accordingly, derivatives such as "Little Russian" (Russian: Малоросс, romanized: Maloross)[c] were commonly applied to the people, language, and culture of the area. A large part of the region's elite population adopted a Little Russian identity that competed with the local Ukrainian identity. The territories of modern-day southern Ukraine, after being annexed by Russia in the 18th century, became known as Novorossiya ("New Russia").[6]

After the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1917, and with the amalgamation of Ukrainian territories into one administrative unit (the Ukrainian People's Republic and then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic), the term started to recede from common use. Today, the term is anachronistic, and many Ukrainians regard its usage as offensive.[7][8]

Etymology

[edit]

The toponym is adapted from the Greek term, which was used in medieval times by the patriarchs of Constantinople from the beginning of the 14th century.[9][2] The Byzantines accepted the distinction between Μεγάλη Ῥωσσία (Megálē Rhōssía, lit. 'Great Rus, Great Russia'), meaning the northern or outer region, and Μικρὰ Ῥωσσία (Mikrà Rhōssía, lit. 'Little Rus, Little Russia'), meaning the southern or inner region.[10][11] From 1448, the former became ecclesiastically independent as the Russian Orthodox Church based in Moscow declared autocephaly, and from 1458, the latter had its own metropolitans who were approved by the patriarch of Constantinople.[12] Previously, the jurisdiction of the latter had become the metropolis of Halych in 1303.[1] By the early 15th century, the terms disappeared and Great Russia would not re-appear in sources until during the 16th century, while Little Russia would not re-appear until the end of that century.[13]

Initially Little or Lesser meant the nearer part,[5] as after the division of the metropolis (ecclesiastical province) in 1305, a new southwestern metropolis in the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia consisted of only 6 of the 19 former eparchies.[5][1] It later lost its ecclesiastical associations and became a geographical name only.[5] Zygmunt Gloger, in his Geography of Historic Lands of Old Poland (Polish: Geografia historyczna ziem dawnej Polski), describes an alternative view of the term Little in relation to Little Russia, where he compares it to the similar term Little Poland.[14]

In Russian, the notion of Rossiia, which was used as the common designation for the multinational Russian Empire and for the modern Russian state, is closely related to the older terms Rus and russkii.[15] Rossiia is distinguished from the ethnonym russkii, as Rossiia refers to a supranational identity, among them ethnic Russians.[15] During the imperial era, Rossiia referred to a multinational state, while the ethnic term russkii officially included all East Slavs, namely the Great Russians, Little Russians and White Russians.[15] In this sense, the Ukrainians, who were known as Little Russians, were part of an all-Russian identity.[15] The rise of modern Russian nationalism created the concept of an ethnic Russian nation with the political concept of the Russian Empire, which was aimed at a new project of an ethnically homogeneous nation-state.[16]

Historical usage

[edit]

The term was used by Patriarch Callistus I of Constantinople in 1361, when he created two metropolitan sees: Megalē Rosiia (lit. 'Great Rus, Great Russia') and Mikrà Rosiia (lit. 'Little Rus, Little Russia').[17] The former referred to the province of Moscow and Vladimir, while the latter referred to the province of Halych and Kiev.[2] King Casimir III of Poland was called "the king of Lechia and Little Rus".[17] Yuri II Boleslav used the term in a 1335 letter to Dietrich von Altenburg, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, where he styled himself as dux totius Rusiæ Minoris.[17] According to Mykhaylo Hrushevsky, the term was associated with the Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia, and after its downfall, the name ceased to be used.[18]

At the beginning of the 17th century, Ukrainian churchmen studying Greek sources took up the term Malorossiia and introduced it into the title of the metropolitan of Kiev, who was elected in 1620.[2] At the time, the term Little Russia referred to the East Slavic lands in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, whose inhabitants were also known as Ruthenians or rusyny.[2] The term Great Russia also began to be used by the Ukrainian churchmen in the 1640s when contact with Moscow increased and it was subsequently adopted in Russia.[2] In 1654, both Little Russia and Great Russia appeared in the title of the Muscovite tsar for the first time.[2] This was preceded by the Cossack Hetmanate falling under Russian protection.[1] From this point on, the Russian government used the term Little Russia to express the idea that left-bank Ukraine and later other regions of Ukraine belonged to Russia.[2]

The term has been used in letters of Cossack hetmans, particularly Bohdan Khmelnytsky,[19] as well as Ivan Sirko.[20][21] Innokentiy Gizel, the archimandrite of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, wrote that the Russian people were a union of three branches—Great Russia, Little Russia, and White Russia—under the sole legal authority of the Muscovite tsars. The term Little Russia has also been used in Ukrainian chronicles written by Samiilo Velychko, as well as in a chronicle of the hieromonk Leontiy (Bobolinski), and in Thesaurus by the archimandrite Ioannikiy (Golyatovsky).[22][23]

From 1762, Little Russia represented the Cossack Hetmanate in left-bank Ukraine, or more precisely, its elites, who had aimed to acquire equal rights with Great Russia in the framework of the Russian Empire.[2] At the time, Great Russia referred to the area of Russia inhabited by ethnic Russians.[2] The usage of the name was later broadened to apply loosely to the parts of right-bank Ukraine when it was annexed by Russia at the end of the 18th century upon the partitions of Poland. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Russian Imperial administrative units known as the Little Russian Governorate and eponymous General Governorship were formed and existed for several decades before being split and renamed in subsequent administrative reforms.[citation needed]

Up to the very end of the 19th century, Little Russia was the prevailing term for much of the modern territory of Ukraine that was part of the Russian Empire, as well as for its people and their language. This can be seen from its usage in numerous scholarly, literary and artistic works. Ukrainophile historians Mykhaylo Maksymovych, Mykola Kostomarov, Dmytro Bahaliy, and Volodymyr Antonovych acknowledged the fact that during the Russo-Polish wars, Ukraine had only a geographical meaning, referring to the borderlands of both states, but Little Russia was the ethnonym of Little (Southern) Russian people.[24][25] In his work Two Russian Nationalities, Kostomarov uses Southern Rus and Little Russia interchangeably.[24][26] Mykhailo Drahomanov titled his first fundamental historic work Little Russia in Its literature (1867–1870).[27]

The Little Russians (Ukrainians) were widely regarded by educated Russians at the start of the 20th century as an integral part of the Russian nation.[16] Assimilation to Russian language and culture among Ukrainian elites was common from the 18th century, but after the 1863 January Uprising in Poland, the Russification of Ukrainians became an explicit goal of the Russian government.[16] The Russophiles of Galicia in the Austrian Empire also advocated for merging into the Russian nation.[16] The Galician Russophiles were the most important branch of the Ruthenian national movement for decades.[16] As a result, if Russification had been successful, Ukrainian nation building could have ended or at least have been interrupted.[16]

The name Ukraine was reintroduced in the 19th century by several writers making a conscious effort to awaken Ukrainian national awareness.[28] At the same time, Little Russia began to acquire its pejorative meaning as the inferior part of Russia.[15] The name Malorossy ("Little Russians") was later used by nationally conscious Ukrainians as a negative term for those who were loyal to the Russian Empire and had integrated themselves into Russian culture and language.[15] By the early 20th century, the terms Ukraine and Ukrainians had become the common self-designation, while Ukraine has been used as an official name since 1917, at first for the Ukrainian People's Republic, then the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.[15] After World War II, the term Ukraine included Ruthenians in Western Ukraine and all Ukrainian-speaking territories were united into one polity for the first time.[15]

Modern usage

[edit]The term Little Russia is now anachronistic when used to refer to the country Ukraine and the modern Ukrainian nation, its language, culture, etc. Such usage is typically perceived as conveying an imperialist view that the Ukrainian territory and people ("Little Russians") belong to "one, indivisible Russia".[29] Today, many Ukrainians consider the term disparaging, indicative of Russian suppression of Ukrainian identity and language.

It has continued to be used in Russian nationalist discourse, in which modern Ukrainians are presented as a single people in a united Russian nation. This has provoked new hostility toward and disapproval of the term by many Ukrainians.[citation needed] In July 2021 Vladimir Putin published a 7000-word essay, a large part of which was devoted to expounding these views.[30][non-primary source needed]

"Little Russianness"

[edit]The concept of "Little Russianness" (Ukrainian: малоросійство, romanized: malorosiistvo) is defined by some Ukrainian authors as a provincial complex they see in parts of the Ukrainian community due to its lengthy existence within the Russian Empire. They describe it as an "indifferent, and sometimes a negative stance towards Ukrainian national-statehood traditions and aspirations, and often as active support of Russian culture and of Russian imperial policies".[31] Mykhailo Drahomanov, who used the terms Little Russia and Little Russian in his historical works,[27] applied the term Little Russianness to Russified Ukrainians, whose national character was formed under "alien pressure and influence" and who consequently adopted the "worse qualities of other nationalities and lost the better ones of their own".[31] Ukrainian conservative ideologue and politician Vyacheslav Lypynsky defined the term as "the malaise of statelessness".[32] The same inferiority complex has been said to apply to the Ukrainians of Galicia with respect to Poland (gente ruthenus, natione polonus).[33] The related term Madiarony has been used to describe Magyarized Rusyns in Carpathian Ruthenia who advocated for the union of that region with Hungary.[31]

The term "Little Russians" has also been used to denote stereotypically uneducated, rustic Ukrainians exhibiting little or no self-esteem. The uncouth stage persona of popular Ukrainian singer and performer Andriy Mykhailovych Danylko is an embodiment of this stereotype; his Surzhyk-speaking drag persona Verka Serduchka has also been seen as perpetuating this demeaning image.[34][35] Danylko himself usually laughs off such criticism of his work, and many art critics argue that his success with the Ukrainian public is rooted in the unquestionable authenticity of his presentation.[36]

In popular culture

[edit]Tchaikovsky's Symphony No 2 in C minor, Op 17, is nicknamed the "Little Russian" from its use of Ukrainian folk tunes.[37] According to historian Harlow Robinson, Nikolay Kashkin, a friend of the composer as well as a well-known musical critic in Moscow, "suggested the moniker in his 1896 book Memories of Tchaikovsky."[38]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Russian: Малороссия, romanized: Malorossiya; Ukrainian: Малоросія, romanized: Malorosiia.

- ^ Russian: Малая Русь, romanized: Malaya Rus; Ukrainian: Мала Русь, romanized: Mala Rus, from Greek: Μικρὰ Ῥωσία, romanized: Mikrá Rosía).[1]

- ^ Plural: малороссы, malorossy. Alternatively: малороссиянин, malorossiyanin, малорус, malorus

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Magocsi 2010, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kappeler 2010, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Kohut, Zenon Eugene (1986). "The Development of a Little Russian Identity and Ukrainian Nationbuilding". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 10 (3/4): 559–576. JSTOR 41036271. Archived from the original on 2023-05-27. Retrieved 2022-11-02 – via 563.

- ^ Kappeler 2010, p. 36, "Since the fourteenth century the Orthodox patriarch of Constantinople designated two church provinces of Rus', Halych/Kiev and Vladimir/Moscow, with the terms he mikra Rosia (Little Russia which is inner or southern Russia) and he megale Rosia (Great Russia which is outer or northern Russia)".

- ^ a b c d (in Russian) Соловьев А. В. Великая, Малая и Белая Русь Archived 2018-05-16 at the Wayback Machine // Вопросы истории. – М.: Изд-во АН СССР, 1947. – № 7. – С. 24–38.

- ^ Schlegel, Simon (2019). Making ethnicity in southern Bessarabia: tracing the histories of an ambiguous concept in a contested land. Leiden. p. 33. ISBN 9789004408029.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Russia rejects new Donetsk rebel 'state'". BBC News. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Steele, Jonathan (1994). Eternal Russia: Yeltsin, Gorbachev, and the Mirage of Democracy. Harvard University Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-674-26837-1. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

Several centuries later, when Moscow became the main colonizing force, Ukrainians were given a label which they were to find insulting. [...] The Russians of Muscovy [...] were the 'Great Russians'. Ukraine was called 'Little Russia', or Malorus. Although the phrase was geographical in origin, it could not help being felt by Ukrainian nationalists as demeaning.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, p. 159, As early as at the beginning of the fourteenth century, Constantinople accepted the distinction between what it designated as the eparchies of Great Rus'... and Little Rus'....

- ^ Kappeler 2010, p. 36, "...with the terms he mikra Rosia (Little Russia which is inner or southern Russia) and he megale Rosia (Great Russia which is outer or northern Russia)".

- ^ Vasmer, Max (1986). Etymological dictionary of the Russian language (in Russian). Vol. 1. Moscow: Progress. p. 289. Archived from the original on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ Magocsi 2010, pp. 159–160, ...a step which eventually led to its complete independence as the Russian Orthodox Church... on Belarusan and Ukrainian lands within Lithuania and Poland, it too, beginning in 1458 had its own metropolitans of Kiev.

- ^ Kappeler 2010, p. 36, "The term Great Russia begins to reappear in sources during the sixteenth century, the term ‘Little Russia by its very end".

- ^ Zygmunt Gloger. Province of Little Poland (Prowincya Małopolska) Archived 2021-04-17 at the Wayback Machine. Geography of historic lands of the Old Poland.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kappeler 2010, p. 37.

- ^ a b c d e f Kappeler 2010, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Русина О. В. Україна під татарами і Литвою. – Київ: Видавничий дім «Альтернативи» (1998), ISBN 966-7217-56-6 – с. 274.

- ^ Грушевський М.С. Історія України-Руси, том I, К. 1994, "Наукова думка", с. 1–2. ISBN 5-12-002468-8

- ^ «…Самой столицы Киева, також части сие Малые Руси нашия». "Воссоединение Украины с Россией. Документы и материалы в трех томах", т. III, изд-во АН СССР, М.-Л. 1953, № 147, LCCN 54-28024, с. 257.

- ^ Яворницкий Д.И. История запорожских казаков. Т.2. К.: Наукова думка, 1990. 660 с. ISBN 5-12-001243-4 (v.1), ISBN 5-12-002052-6 (v.2), ISBN 5-12-001244-2 (set). Глава двадцать шестая Archived 2007-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Листи Івана Сірка", изд. Института украинской археографии, К. 1995, с. 13 и 16.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-12-24. Retrieved 2018-12-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Русина О. В. Україна під татарами і Литвою. – Київ: Видавничий дім «Альтернативи», 1998. – с. 279.

- ^ a b In his private diary Taras Shevchenko wrote "Little Russia" or "Little Russian" twenty one times, and "Ukraine" 3 times ("Ukrainian" – never) and ("Kozak" – 74). At the same time in his poetry he used only "Ukraine" (and "Ukrainian" – never). Roman Khrapachevsky, Rus`, Little Russia and Ukraine, «Вестник Юго-Западной Руси», № 1, 2006 г.

- ^ s:ru:Дневник (Шевченко)

- ^ Костомаров М. Две русские народности // Основа. – СПб., 1861. – Март.

- ^ a b Михаил Драгоманов, Малороссия в ее словесности Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine, Вестник Европы. – 1870. – Июнь

- ^ Ukrainians Archived 2007-05-03 at the Wayback Machine in the Encyclopedia of Ukraine Archived 2009-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Analysis of the events of the Orange Revolution in Ukraine by Prof. Y. Petrovsky-Shtern Retrieved Archived 2020-02-10 at the Wayback Machine May 23, 2007

- ^ On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians [1] Archived 2022-01-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Ihor Pidkova (editor), Roman Shust (editor), "Dovidnyk z istorii Ukrainy Archived 2009-04-10 at the Wayback Machine", 3-Volumes, "Малоросійство Archived 2007-05-26 at the Wayback Machine" (t. 2), Kiev, 1993–1999, ISBN 5-7707-5190-8 (t. 1), ISBN 5-7707-8552-7 (t. 2), ISBN 966-504-237-8 (t. 3).

- ^ Ihor Hyrych. "Den". Lypynsky on the imperative of political independence Retrieved Archived 2008-05-21 at the Wayback Machine May 23, 2007

- ^ Serhii Plokhy, "The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus" Archived 2023-07-12 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press (2006), ISBN 0-521-86403-8, pp.169-

- ^ (in Ukrainian) Serhiy Hrabovsky. "Telekritika". "Sour Milk of Andriy Danylko" Archived 2008-08-21 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on May 23, 2007

- ^ (in Russian) НРУ: Верка Сердючка – позор Полтавы Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, Korrespondent.net, 22 May 2007

- ^ (in Russian) Алексей Радинский, Полюбить Сердючку Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, Korrespondent, 17 March 2007

- ^ Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995), 87.

- ^ Robinson, Harlow. "Symphony No. 2, Little Russian". www.bso.org. Archived from the original on June 14, 2024. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Kappeler, Andreas (12 July 2010). ""Great Russians" and '"Little Russians"". In Barker, Adele Marie; Grant, Bruce (eds.). The Russia Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 31–39. ISBN 978-0-8223-4648-7.

- Magocsi, Paul R. (1 January 2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7.